Where the chips may fall

all about chips, who makes them, and how they're fueling healthcare

Introduction

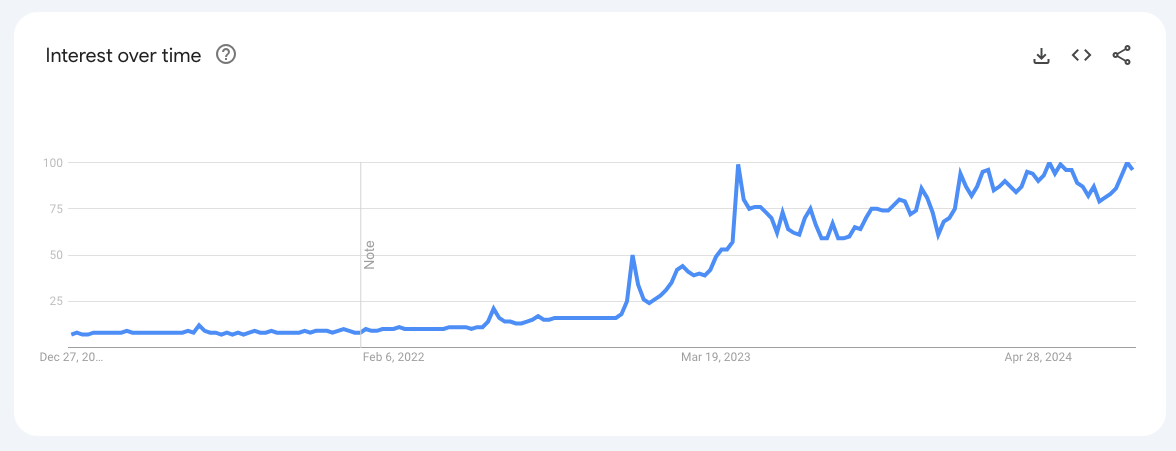

The world is abuzz with talk of artificial intelligence, and for good reason. Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Gemini are capturing imaginations with their ability to generate human-quality text, translate languages, and answer complex questions. But behind these digital feats lies a powerful engine fueled by something quite tangible: chips. Computer chips are the tiny silicon brains behind our digital world.

The two chip types we’ll talk through today are CPUs (Central Processing Units) and GPUs (Graphics Processing Units). CPUs are the general-purpose workhorses, handling a wide range of tasks like running your operating system and the applications on top of it. GPUs are specialized processing chips which excel at parallel processing, making them ideal for visually demanding tasks like gaming and, increasingly, the complex calculations required for AI. As the AI world continues to scale (almost exponentially in usage at this point) it is becoming increasingly obvious how important these chips are to the future success of the field. Let’s dive a little deeper into how CPUs and GPUs are used to build and interact with the AI systems of today.

Eating Chips - How are chips used in AI workloads?

CPUs and GPUs play distinct but interconnected roles in the world of AI, particularly in the crucial phases of training (teaching the model) and serving (offering it to be used by consumers in applications) of these AI models.

Model Training

Think of training an AI model like teaching a student. You use data captured from the real world, feed it through your model architecture, see how well the model learned, adjust and teach it better in the areas it didn't learn well, and then repeat this process over and over until the model is sufficient at the task at hand. Sometimes this is accomplished using relatively classic statistical modeling techniques. When things get more complicated, neural networks are introduced into the mix. This is where GPUs shine. Their parallel architecture makes them incredibly efficient at handling matrix multiplications (the mathematical underpinnings of neural networks) and other computationally intensive operations at the heart of deep learning algorithms. During training, data is fed through the model architecture on the GPU(s), allowing it to learn patterns and relationships. The CPU, while less specialized for this heavy lifting, still plays a vital role, managing data flow, handling system tasks, and orchestrating the overall training process. CPUs also are responsible for transferring the data from SSD / HDD or even in-memory on RAM to the GPU to perform these computations. As you can imagine, the speed and volume at which the GPU can process data can greatly impact the model's quality, velocity of training, power consumption and ultimately the cost produced by this process.

Model Serving

Once trained, an AI model needs to be deployed for real-world use – this is called model serving. Historically, the balance of power often shifted towards CPUs. A model is packaged up (there are a few standard ways of doing this, but I'll spare you the gory details) and wrapped in an API endpoint that receives requests from users typically producing a value estimation or classifying a record based on some input data. While these tasks can leverage GPU acceleration, they often don't demand the same level of raw computational power as training. However, GPUs are increasingly taking center stage in this department these days. While CPUs can handle smaller models or less demanding serving scenarios, the sheer scale and complexity of Large Language Models (LLMs) make GPUs almost indispensable in the serving process. The serving architecture of LLMs can take advantage of the GPUs ability to parallelize work when determining or predicting the next token in a sequence which often requires evaluating thousands of potential next steps. The sheer size of these models also generally exceeds the size supported efficiently by the on-chip memory forcing the need for GPUs. Because of this shift, specialized versions of GPUs optimized for exactly this problem are cropping up from major players like Google.

Companies who are cooking [building] chips

Let's talk more about the companies behind these chips. Let’s look first at who is making CPUs - the general-purpose workhorses of the machines used in AI applications. There are basically only two companies making standalone CPUs - Intel and AMD. These are the legacy players in this space, comprising most of the market. There is a third player - ARM. Most people don’t know of them as a company but rather a CPU architecture that sets out to compete with the x86 instruction set architecture that underpins the Intel and AMD lines of CPUs. While these terms are usually conflated, ARM is the company that owns and licenses the technology to other companies (Apple, Qualcomm, and Samsung, etc.).

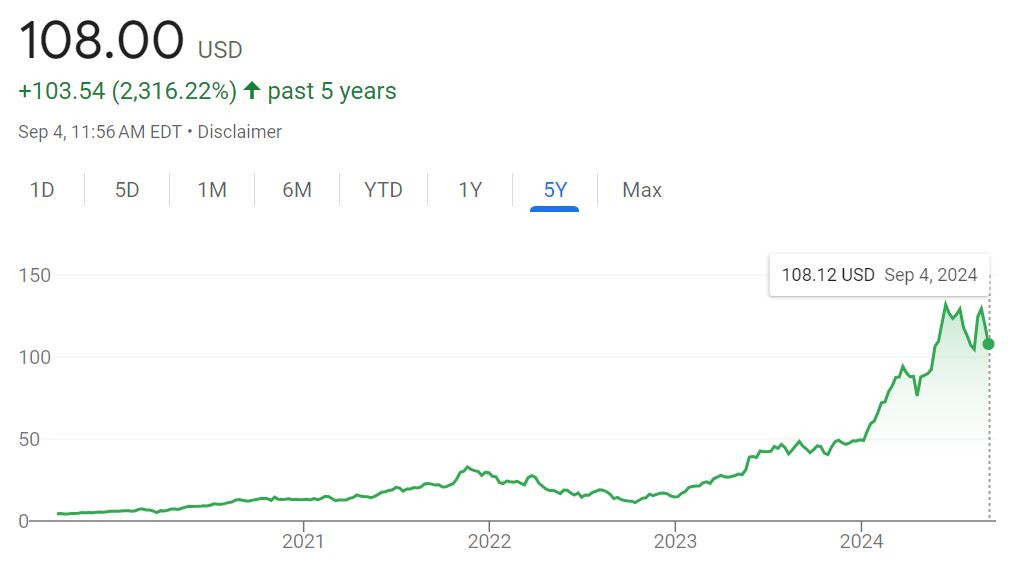

On the GPU side of the house Intel and AMD are shadowed by the largest player in this space, Nvidia. Known originally for building GPUs to support better video rendering experiences, their market share has absolutely exploded in the AI era, with their GPUs becoming foundational to the success of the entire market. To interact with the GPU, the company ships and supports a popular package called Cuda.

Some companies are combining CPUs and GPUs to eliminate some bandwidth constraints stemming from the communication between the two components on a machine. The most notable attempt at this method is Apple’s M-Series of silicon shipping in their newest machines. An interesting strategy that will be one to watch, particularly to see how well it will scale (if at all) outside of a single laptop, or if at some point the cost efficiencies push us back to a componentized architecture.

Lastly, some companies are designing chips specifically for ML tasks. First on this list is the Google designed TPU. This chip was built specifically for efficient interactions between Google’s TensorFlow machine learning package and the hardware. Google is the only company that owns and operates these chips. Other companies such as Graphcore, Cerebras, Hailo, SambaNova, and Groq are all building “AI accelerators.” AI accelerators are specialized hardware designed from the ground up to dramatically speed up artificial intelligence workloads, particularly the training and inference phases of deep learning models. Unlike general-purpose CPUs or even GPUs, which have broader applications, AI accelerators are laser-focused on optimizing the specific computations at the heart of AI algorithms. Alongside this list of startups, you will also see Nvidia Tesla AI accelerators and Intel’s line, which they acquired through the acquisition of Habana Labs. In this camp of specialized hardware, you will see another type of chip emerge – the ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits). Currently they offer the highest performance and efficiency but come with higher development costs and less flexibility.

Where are the ingredients sourced?

There are many chip designers used for machine learning and artificial intelligence applications, but who makes these chips? Well, that’s one of the more interesting (and slightly concerning) pieces of the scaling / supply chain equation. There are largely just two manufacturers who can churn out these high-performance chips at the scale and level of control that is needed by these companies - TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) and Samsung Foundry. As you can imagine this introduces a major chokepoint in the chip supply chain, one that companies downstream are starting to take full advantage of.

Everyone is craving chips

Using (or marketing the use of) AI has become nearly the baseline for companies trying to raise capital from venture funds. AI models are complex and process large amounts of data, which requires chips to train and run AI applications. As mentioned above, GPUs are generally needed to handle the parallel processing required for AI tasks. The costs of these chips vary based on the end market (consumer vs. professional vs. data center), can range anywhere from $150 to over $25,000 per unit from Nvidia. Despite the costs associated with chips, companies can’t get enough. This explains the Nvidia’s stock price, which has soared as AI continues to become omnipresent, amongst small and large companies alike. If you bought 100 shares of the company in August 2019 for $4.19 ($419 total), it would now be worth $10,800 right now - that is a ~25.8x return in 5 years. The stock’s price increase was probably (definitely) a dinner table conversation topic for all of you this summer, for good reason. Nvidia basically has one true competitor - AMD - also a large, publicly traded company. AMD’s stock price has also benefited from everyone’s chip cravings, although not nearly as much as Nvidia has over the same period. If you had purchased 100 shares of AMD 5 years ago instead of Nvidia, you would have made a ~4.6x return. Intel was also a competitor, however given Nvidia’s 80%+ market share and AMD’s ~15-20% market share that has increased over time, Intel has lost a lot of its share in the GPU space.

Given the higher cost of the chips needed to process the data being used in AI applications, early-stage startups may lack the ability to buy them on their own. Big tech companies can offer IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) and CaaS (Compute as a Service) to smaller companies that need processing resources or core infrastructure required to run AI models. Separately, VC fund a16z began stockpiling thousands of chips earlier this year in anticipation of surging demand. They are renting GPUs to startups in exchange for equity, giving the fund more exposure to the emerging AI landscape. The fund is also invested in OpenAI and xAI, companies that have raised over $11B and $6B to date. OpenAI, founded in 2015 and run by Sam Altman, gained popularity seemingly overnight for its ChatGPT model. The company is developing AI products for all kinds of end users. xAI, founded in 2023 by Elon Musk (who is also a co-founder of OpenAI), is a newer company focused on developing AI systems to accelerate human scientific discovery. All of these companies are craving chips, and are willing to pay for them.

Quantumania

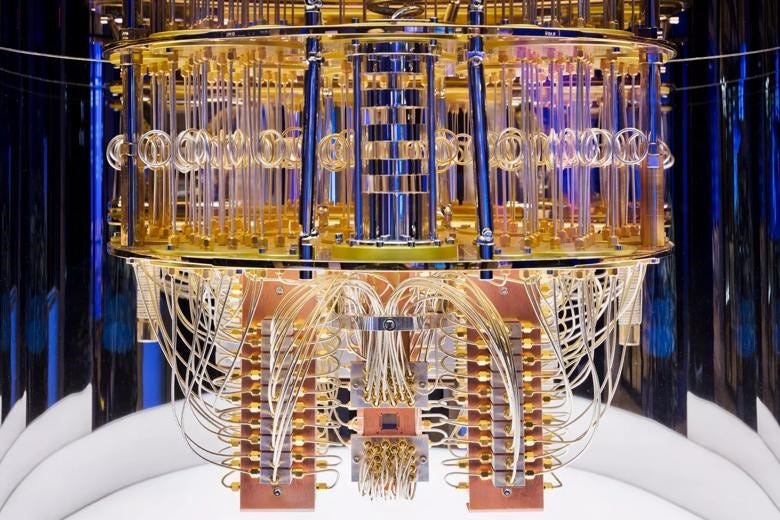

Part of the excitement around advancements in chip technology comes from the rise of quantum computing capabilities. Quantum computing is still a relatively new concept, pulling from the basis of quantum mechanics, where at the subatomic scale, matter and light can exist in multiple states at the same time, such as a particle and a wave. Assessing matter and light at the quantum level enabled a branch of physics that explored beyond the binary. Similarly, a quantum computer’s subatomic components, called qubits, take us beyond the optionality of a mere coin flip. Unlike regular bits which exist as either 0 or 1, qubits can exist in a state of 0, 1, or both simultaneously, significantly expanding the computational space possible. That can be a lot to take in, but don’t be salty; all it amounts to is that when we’re talking quantum, we’re talking about something exceptionally small with a big impact.

Classical computers are unable to address some of these more highly complex problems because they process information sequentially, one bit at a time. As mentioned above, they use CPUs and GPUs, while quantum computers rely on specialized chips known as quantum processing units (QPUs), which house qubits as circuit elements on the chip. Creating those qubits inside the QPU is part of the challenge of developing quantum computers at scale. Essentially, for superconducting qubits, the principles of quantum mechanics are applied to the electric circuit so that electrons pass through a junction (Josephson Junction) made by sandwiching a layer of non-superconducting material between two superconducting materials. Many of these junctions exist in a QPU, and the chips have to be kept at extremely low temperatures to maintain stability. Because of the energy and power requirements, building these quantum computers is no small feat. However, once functioning, the resulting computational power far exceeds anything we have seen at the classical bit level.

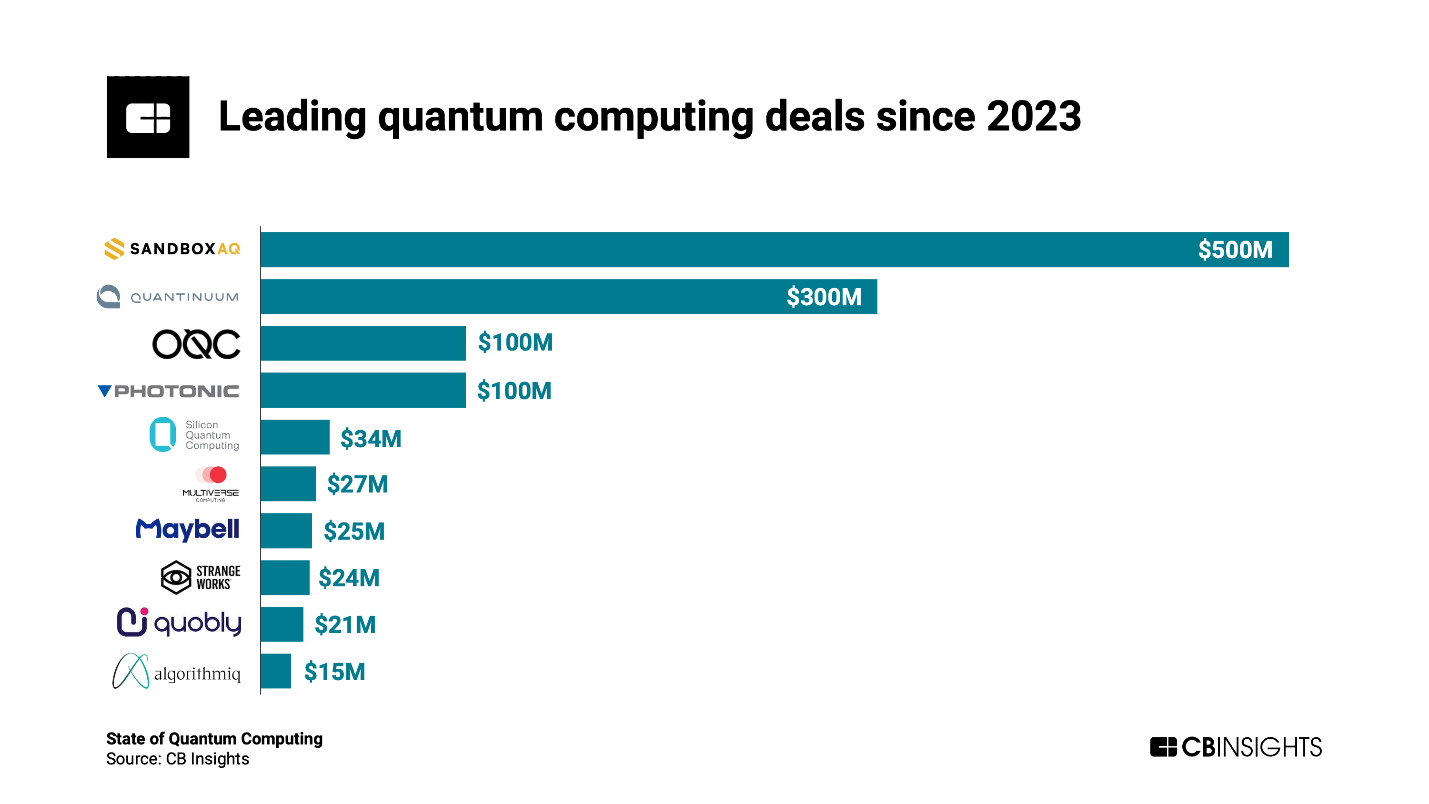

Quantum computing holds the potential to tackle extremely complicated problems, including personalized drug development via complex chemical reaction analysis, optimization algorithms across industries, and development of highly secure encryption algorithms. The potential to develop solutions across these and many other use cases has driven funding in this space in a steadily upward trajectory. Funding in 2023 reached $1.3B, marking a 20% increase YoY. This is an interesting juxtaposition to the general decrease in venture funding across the board. Much like the AI boom, investors and startups alike are committing to investing in quantum computing and chip technology advancements.

Are chips healthy?

There are lots of different kinds of chips, some healthier than others. Earlier this year, Mayo Clinic announced that they would be using Cerebras chips for their LLMs. Cerebras Systems has raised over $700M and was valued at $4.3B in 2021, and they compete with Nvidia in some cases (for context, Nvidia’s market cap is over $2T). Nvidia is partnering with GE Healthcare to bring AI to imaging devices. They are also working with J&J to innovate operating rooms. Medtech companies also rely on chips to manufacture their products, and struggle when supply chain issues worsen.

The surge in quantum computing holds potential across industries, very much including healthcare. Everyone wants a slice of the quantum chip pie (à la mode), and health systems are no different. Recently, IBM and Cleveland Clinic unveiled an exciting 10-year partnership centered around enabling healthcare research via quantum computing. The teams are working together using an IBM Quantum System One computer at Cleveland Clinic’s main campus. Some of the projects the partnership will seek to address include optimizing drugs targeted to specific proteins, quantum-enhanced prediction models for cardiovascular risk, and AI-enabled genome sequencing analyses to help patients with Alzheimer’s. Since the announcement of their Discovery Accelerator partnership, IBM and Cleveland Clinic have also started a collaboration with the Hartree Centre in the UK to apply quantum computing to large-scale dataset analysis in order to better understand molecular features in the body that may reveal likely surgical responses in patients with epilepsy.

It's clear that healthcare companies are craving chips just like the rest of us, for good reason. As applications for AI continue to expand across healthcare and other industries, we expect demand for chips of all kinds to grow.